Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Archival Collections Document the Black Arts Movement in 20th-century Pittsburgh

The musicians, beating on the djembe and dundun drums, made the call. The dancers sprang forth. All were paying homage to the movement and culture of Mali, but also to Bob “B.J.” Johnson, the former University of Pittsburgh teacher, performer and dance company founder who helped to bring the rhythms and lessons of Africa to the campus and community.

Family, friends, professors and former students attended a dedication at the Hillman Library in September to recognize the legacy of Johnson, a director and choreographer whose papers make up one of two African-American performing arts archival collections recently donated to the University of Pittsburgh.

The Johnson collection comes from his family and from the Pittsburgh Black Theatre Dance Ensemble, founded in 1970 by Johnson. The second new collection comes from the Kuntu Repertory Theatre. Kuntu, a central African term meaning “way” or “mode,” was founded in 1974 and overseen for 40 years by Vernell Lillie, a nationally recognized director and former professor in Pitt’s Africana Studies department.

Both collections help document the growth of the University’s Africana Studies department, born as the Black Studies program in 1969. But they also capture the power and scope of the larger Black Arts Movement, which is based on the belief that the arts can educate, address social justice issues and change society.

“The Kuntu Theatre and B.J. Johnson saw themselves as part of the Black Arts Movement,” said Larry Glasco, a professor of history at Pitt. “They produced locally, but they were part of the larger movement that believed that dance, music, theater, literary arts went together.”

The Johnson and Kuntu papers fall under the umbrella of Pitt’s Curtis Theatre Collection, which documents Pittsburgh’s rich theater history, now adding an African-American angle.

“Pittsburgh’s African-American performing arts have not been well documented,” said Bill Daw, curator of Pitt’s Curtis Theatre Collection. “Pitt is actively trying to fill that gap. Our goal is to promote research into these collections so the history of the African-American performing arts in Pittsburgh is acknowledged.”

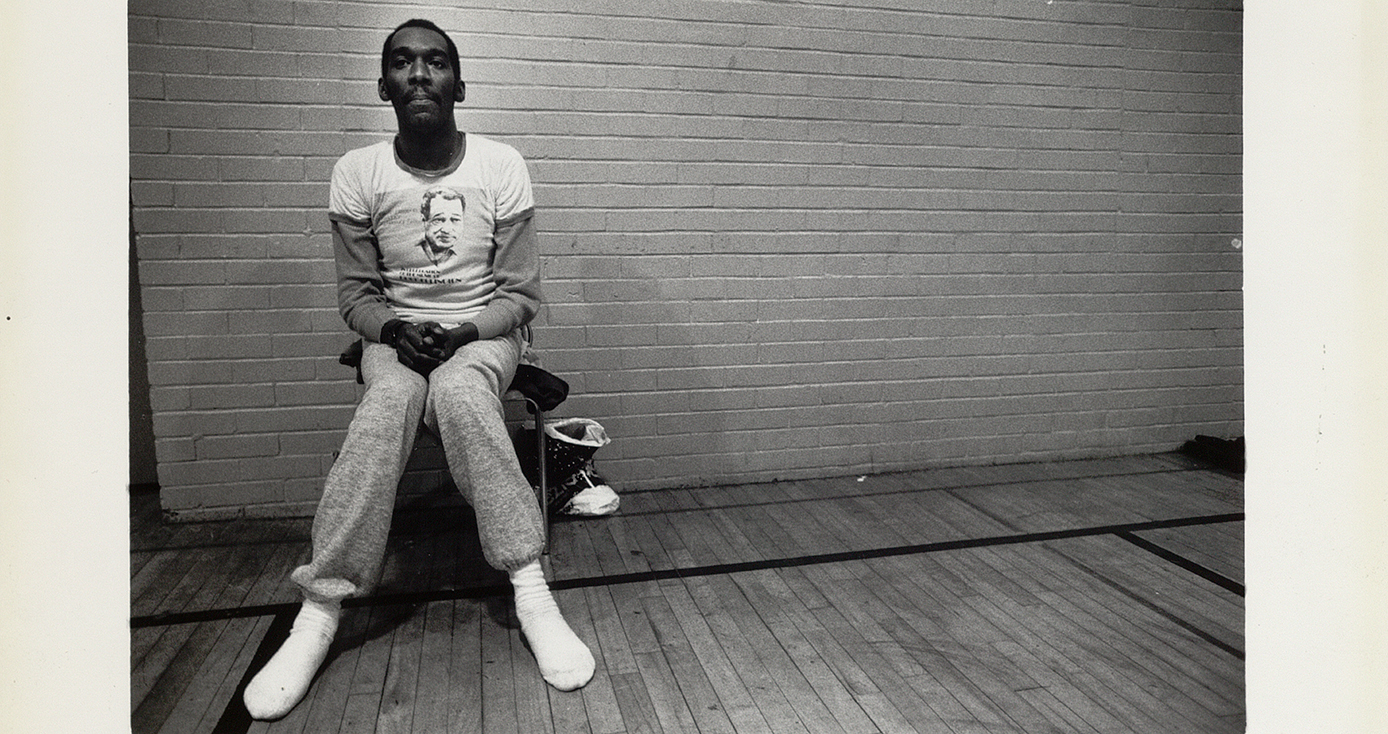

Bob “B.J.” Johnson

In the winter of 2013, Johnson’s daughter, Marimba Johnson Bright, named for an African goddess, and his son, Samba, named after an Afro-Brazilian dance, reached out to Pitt, interested in donating their father’s papers to the University. They were continuing the conversation begun in 1996 by their mother, Stephanie Johnson, who felt her husband’s life and work were integral to the history of the Black Studies department and the University and that his documents should be made accessible.

“In Pittsburgh, my father used dance as activism to change people and the community,” said Johnson Bright. “We can’t imagine the papers going anywhere else except for Pitt. We are hoping people will come in and use the archives to understand my dad’s legacy.”

Johnson, who died in 1986, was born in 1938 in Brooklyn. He trained at New York’s Metropolitan High School for the Performing Arts, and went on to study with such noted choreographers as Alvin Ailey, Katherine Dunham and the June Taylor Dancers.

In 1970, he joined the Black Studies department at the University, using his position to strengthen Pitt’s outreach to the community.

“He believed his body was an instrument,” said Malaya Rucker, who danced with Johnson and who spoke at the September celebration.

The material in the collection dates from 1949 to 2003, including press clippings and tributes written after his death.

Meaghan Alston, a former Pitt archivist, was first assigned to organize the Johnson collection. As she pored over the material, she felt the “weight” of Johnson’s beliefs, as his letters and correspondence revealed that through dance there was a deeper culture that united Black Americans to West Africa and the Caribbean and that dance could tell those important stories.

“The philosophy of the Black Arts Movement was all there,” she said.

She also said she was impressed with his bravery. For example, for America’s bicentennial in 1976, Johnson produced a piece called “American Fruit with African Roots,” which portrayed dancers in blackface and slave costumes. It was provocative, Alston said, but he used dance and theater to tell the story of Black people in America, and he believed that art could be political and educate and empower.

“My father,” said Johnson Bright, “was a warrior in the Black Arts culture of the city of Pittsburgh and through dance and theater he was able to express his ideas on nationalism, politics and African values.”

Johnson also directed several early versions of Pulitzer Prize-winner August Wilson’s plays. In 1982, he was director for the first staged production of Wilson’s “Jitney.”

The Kuntu Repertory Theatre

Kuntu was the creation of Vernell Lillie, a Texas native and teacher who came to Pittsburgh to earn a doctorate in theater at Carnegie Mellon University.

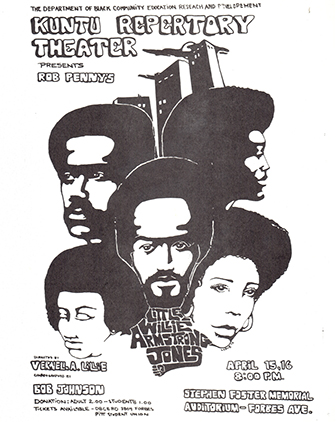

In 1973, she was recruited to teach and write grant proposals for the Black Studies department at Pitt. A year later, Lillie and Rob Penny, a fellow Black Studies colleague and a prolific poet and playwright, founded Kuntu Repertory. Lillie was impressed by Penny’s plays and used Kuntu to give his works life.

Kuntu included students, professional actors and members of the community. They performed in the Stephen Foster Memorial Theatre and then at Alumni Hall auditorium, both at Pitt.

Kuntu lasted for nearly 40 years, became a showcase for Black actors and playwrights and helped to launch the careers of Wilson and scores of local actors. Kuntu’s final performances were in the Homewood Library auditorium in 2013.

Work on the Kuntu collection began in 2015. Lillie retired from the University in 2006, but Pitt worked with her family and faculty members to gather documents from the basement of her Pittsburgh home and from department files. There are more than 500 boxes of material.

There are faculty papers and correspondence with students, actors and directors. There are posters, playbills and other ephemera. The collection also details Lillie’s work in Africa and her collaborations with Woodie King Jr., director and founder of the New Federal Theater in New York, and Emmy Award-winning actress Esther Rolle, whom she invited to perform in “Raisin in the Sun” for Kuntu’s 10th anniversy, said Megan Massanelli, the Pitt archivist who is in the early stages of organizing the material.

The collection, said Ed Galloway, interim assistant university librarian for archives and special collections, showcases the arc of Kuntu. From its beginnings to its production of psychodrama to capturing issues of race and class discrimination, Kuntu used music and African themes to comment on Black life and history and to urge social action.

The Black Arts Movement

The Black Arts Movement began in the mid-1960s and fanned out across cities such as Philadelphia, Atlanta, Detroit, Chicago — and Pittsburgh.

Unlike its predecessor, the Harlem Renaissance, which was intellectually and artistically centered in that storied New York neighborhood, the movement was decentralized.

It had such significance in Pittsburgh largely because of artists such as Bob “B.J.” Johnson, Vernell Lillie and Rob Penny, who believed in taking their cutting-edge ideas to the people, said Pitt history professor Larry Glasco.

The three were colleagues and friends. And Penny was good friends with August Wilson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who grew up in the Hill District neighborhood of Pittsburgh and participated in early Kuntu writing projects and theater.

“In the Black Arts Movement, they were talking to Black audiences, the everyday people,” said Glasco. “They were among the vanguard of the explosion of African-American art in the city and across the nation.”