Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Pittsburgh as a Human Performance City

This excerpt, written by Elaine Vitone, is from the spring 2019 issue of Pitt Med magazine, the School of Medicine’s quarterly publication.

For U.S. Army truck drivers on major supply routes in Afghanistan, a daily commute amounts to several anxious hours in a convoy of dozens of vehicles. Every morning, they wake up knowing they will be attacked on that road to Bagram Airfield. They know because it’s happened to them before — 30, 40, even 50 times.

A truck might be hit by an IED, says the University of Pittsburgh’s Ronald Poropatich. Or, just as dangerous is when a driver falls asleep at the wheel. “That happens a lot,” says Poropatich. So the soldiers get hurt or die because of a simple thing we all take for granted: sleep.

Other service members commute via “HALO” jump — high altitude (maybe 30,000 feet, to evade radar), low opening (at 1,500 feet, BAM! open chute). They hurl themselves out of a jet to certain danger behind enemy lines, hooked up to an oxygen mask. Because the air is thin those miles above the Earth.

Dangerous doesn’t even begin to cover it.

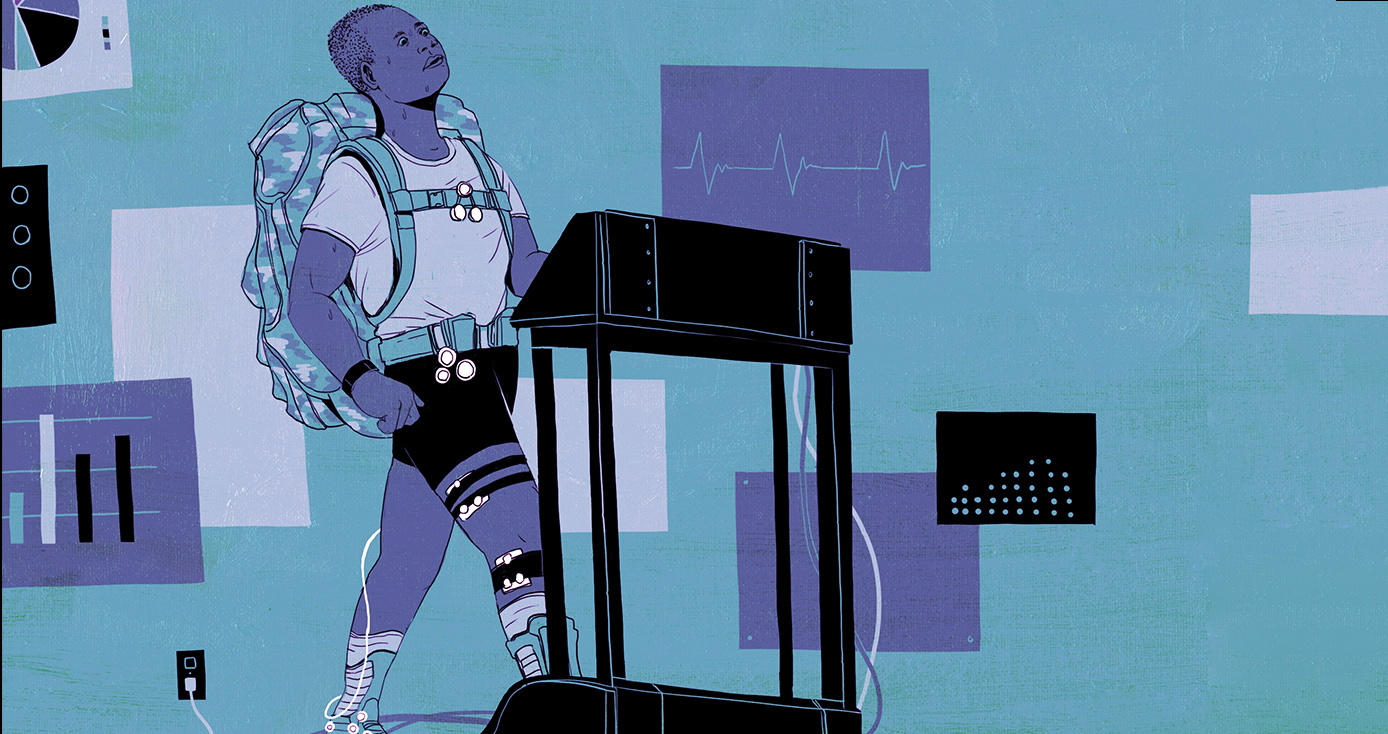

But as it turns out, the most common reasons for American soldiers to be medically evacuated from combat theater today are not injuries from jumping from planes or taking enemy fire. They’re musculoskeletal injuries, but largely from training and carrying around a rucksack.

Everyday wear and tear on the joints. Sleep, or lack thereof. Both the mundane and the obviously death-defying can do us in.

How do we keep ticking? Researchers in a growing field known as human performance optimization want to know how we can function at our best even when our circumstances aren’t. Human performance is a crucial concern for the American military, says Poropatich, director of Pitt’s Center for Military Medicine Research (CMMR), which works closely with the Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense (DOD) research arms to solve military medical problems.

But improving performance isn’t just in the interest of service members, of course. “There are lots of people at Pitt” chasing down this goal, says Rory Cooper, “whether it’s post-transplant, or post-spinal cord injury, or amputation, or our own Division I athletes, or special operations forces.”

Cooper himself, founder of the Human Engineering Research Laboratories (HERL) and Distinguished Professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Science and Technology in Pitt’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, has garnered numerous awards for his contributions to assistive technology, a field that enhances daily living for persons with disabilities. He’s also an elite athlete, medaling in the Paralympics and National Veterans Wheelchair Games year after year. (He’s racked up 150 Wheelchair Games medals.)

In June, Pitt will host a national conference on human performance optimization, organized by collaborators across the health sciences. In September, the DOD will join in on a two-day meeting with Poropatich and others at Pitt to discuss how academia can fill in gaps in the DOD’s own efforts. “To open their eyes to areas of human performance optimization that they’re not currently thinking about,” says Poropatich.

Across campus, with full support from University leadership — notably, Chancellor Patrick Gallagher — a movement is afoot to plant a flag here and unify disparate and complementary human performance efforts more formally. In October 2018, Pitt released a 30-year master plan that includes a massive redevelopment of the athletic campus; a Human Performance Center features prominently in a new area dubbed Victory Heights.

When scientists study a disease, they often start with the most extreme cases and work their way back. In the study of our physicality and its limits, soldiers and elite athletes are super users. And at Pitt, both are in abundance: Service members and veterans have been volunteering for Pitt studies for years. A number of national sports franchises are expressing interest in partnering with the University. And NCAA Division I athletes are just outside the doors of Pitt scientists.

Pitt, it seems, is uniquely positioned to anchor Pittsburgh as a Human Performance City.

There’s more to the story. Read the rest of the Pitt Med feature about how we’re optimizing human performance.