Nothing quite stymies aging experts like the staircase.

Getting an older climber from bottom to top — or top to bottom — safely has been the focus of thousands of products and investigations over the decades.

The go-to solution, the stairlift, has long been the gold standard, but it’s not without its flaws. It’s large and obtrusive and can be prohibitively expensive. Other products, like moving grab bars and climbing canes, aren’t widely available or don’t provide enough support.

So SafeStep, a cable-driven handrail akin to a ski slope tow rope, was poised to be an industry gamechanger.

Developed by an interdisciplinary team of engineers and clinicians at the University of Pittsburgh, SafeStep avoids the pitfalls that have plagued other similar innovations. The system is modular and low cost, so it fits into nearly any home or budget. It’s also low profile, so it doesn’t become a household tripping hazard. After successful trials in Pitt’s labs at Bakery Square in East Liberty, the team was ready to assess SafeStep in a more realistic setting. So, they loaded it up and drove it over to 257 Oakland Ave.

At first glance, the three-story, red brick house in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood looks like any other family home in the city. But since purchasing it in 2022, Pitt has transformed the 1860s-era house into a first-of-its-kind proving ground for aging in place.

They call it the Healthy Home Lab (HHL), and it is where an interprofessional team tests the aging-in-place technology it develops. In this case, the home’s steep, narrow staircase helped to expose important design shortcomings and inform the next round of improvements for SafeStep — its cables would need to be stiffer and the system more responsive for climbers with limited mobility or sluggish reflexes.

“The house keeps us honest,” says Pam Toto, a professor in Pitt’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the director of the Healthy Home Lab. “For us, it’s crucial that what’s developed in the lab can be used in the community. If we can’t deploy it, if we can’t get it into the hands of those who need it, then we’re just a fancy lab in an old house.”

The aging conundrum

The idea for the Healthy Home Lab started with Everette James. He was fresh off a stint as Pennsylvania’s secretary of health when he accepted the position as Pitt’s associate vice chancellor for health policy and planning and director of the Health Policy Institute. The dual roles offered him a panoramic view of the University’s research landscape, and he immediately recognized an expertise in aging and mobility. Pitt researchers had already made important advancements in mobility devices, stroke recovery and Alzheimer’s disease detection, to name just a few.

But that expertise was scattered across schools and departments, from engineering and computer science to medicine, nursing and occupational therapy. James believed collaboration between these experts could lead to more creative ideas and larger leaps. So, he identified key players who could help to assemble an interprofessional team able to translate aging-in-place ideas into ready-to-use solutions — and fast.

“Supporting our aging population is not a futuristic challenge; it’s here today,” James says.

According to U.S. Census Bureau calculations, nearly a quarter of Americans will be over 65 by 2050, and the country isn’t prepared for it. A recent AARP survey shows 75% of older adults want to stay in their homes as they age, but only 10% of those homes are what the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development would deem “aging-ready.” Most homes in the United States lack a step-free entryway or a bedroom and bathroom on the first floor, factors that complicate mobility, independence and — ultimately — quality of life.

The problem is particularly pronounced in Pittsburgh, where more than 56% of the over-65 population stay in their home for more than 30 years — with no plans to move out.

Home sweet home

One of those aging Pittsburghers who had no desire to leave his home was Emmanuel Supertzi, the former owner of 257 Oakland Ave.

He grew up there under the watchful eyes of his Greek immigrant parents and a rotating cast of aunts, uncles and cousins who rented out the third floor. Then he returned to raise his own children there after his wife died suddenly of cancer at the age of 24.

Just as he had done, Supertzi’s children made that house their own. They rode the wooden banister from the second floor to the first and hid in the empty darkness under the staircase. They ate their grandmother’s fried chicken in the dining room and played until dusk in the backyard.

With so many memories living inside its walls, Supertzi made no plans to leave that house, even after his children grew up and his parents passed on. As the years ticked by, the steps seemed to get steeper and the home’s upkeep more cumbersome. He simply shrank the house around him until it fit, moving his bed to the dining room and closing off the second and third floors so he didn’t have to pay to heat them.

“He could not leave this house,” his daughter, Nancy Supertzi Werder, says.

Supertzi died in 1997. But just like their dad, his children couldn’t bring themselves to part with the house. It wasn’t until Pitt approached the family in 2022 with a proposal to purchase the property and turn it into the Healthy Home Lab that they finally agreed it was time to let go. What better way to honor their father than to have his beloved home help others stay in theirs.

“The idea to help people stay in their homes longer — it’s great,” says Supertzi’s daughter-in-law Francine Supertzi. “It made selling the house a lot easier on the family.”

Today, the house doesn’t look much different than it did when Supertzi lived there — by design. Toto’s occupational therapy students decorated it with thrift store finds so that it looks and functions like a typical home with familiar hazards: A wrinkled area rug is a tripping threat. A low couch is awfully difficult to get in and out of. Light switches can be impossible to locate in the dark.

“It was critical that the house looked like a real home and had some of the problems that real homes have,” says Toto, “because how would our engineers and our students and the community be able to identify the issues and offer ideas for solutions if we didn’t have problems?”

Making change

The Healthy Home Lab may be purposely packed with problems, but it’s steadily filling with solutions, too.

Toto likes to categorize those solutions into three arms: research, education and community. The research arm of the operation is the one that gets the most attention. The team has already secured three large federal grants and created a patent-pending adjustable rail system known as Mobius .

But researchers also test existing products and offer feedback to their developers, helping to improve solutions and expedite their path to market. The Healthy Home Lab was recently designated by the AARP as a national testbed for aging-in-place products.

The education arm has quickly become vital to graduating skilled technicians, Toto says. In the two years the Healthy Home Lab has been in operation, students from more than a half dozen disciplines, including occupational therapy, pharmacy, medicine, emergency medicine, audiology, rehabilitation technology and engineering, have used the house as a classroom and training center. While seeing and experiencing the challenges facing older adults is eye-opening for many of the budding professionals, it better prepares them for what they may face in their careers.

But the most important arm, by Toto’s estimation, is community. Without partners like the Area Agency on Aging, Age-Friendly Greater Pittsburgh and Women for a Healthy Environment, among others, it would be nearly impossible to get solutions to the people who need them. These agencies are the mechanisms for getting products into the community.

“The Healthy Home Lab is an example of a project that is intricately linked to all parts of the Pitt mission — the resources are here, the talent’s here and the community partnerships are here,” says the home’s technical director Jon Pearlman, who was part of James’ initial team. “I hope people see that we’re really trying to make a difference, not just by writing a paper, but actually by seeing community change and community improvement based on the work that we’re doing.”

A closer look at the tech (and potential trouble spots) tested by Healthy Home Lab researchers

Living room

(1) Lightbulb moment: A ceiling light with a camera inside can call for help if it sees a fall, but it’s not 100% accurate. HHL testers say it gets a lot of false negatives — and a few false positives, too.

(2) Up and at ’em: A sturdy security pole can help people sit and stand easily, but they’re not all made equal. The HHL team had to modify this one to anchor it to the high ceilings.

(3) Warning: A rug with elevated edges that could pose a trip hazard to some.

(4) Too low: A low-profile sofa that begs the question: If you sit down, will you be able to get back up?

(5) Community Partnership: Members of the HHL team, led by Steve Albert in the School of Public Health, joined the Area Agency on Aging along with Women for a Healthy Environment to test and distribute commercially available air quality monitors—because sometimes the household hazard is one you can’t see. They piloted the monitoring project in more than 40 Pittsburgh-area homes and built a program that can be used by others to assess mold or air quality issues and supply air purifiers.

Dining room

(1) Easy there: Sometimes the simplest solutions are the most effective. By replacing the type of pulls on this china cabinet, the HHL team made the drawers easier to open and close, particularly for those who may lack strength or flexibility in their fingers.

(2) Nothing off the table: HHL engineer Todd Hargroder designed this wheelchair-friendly table so that users could slide in anywhere, not just the end. It also has a lip on the underside to help non-wheelchair users stand up after a meal.

(3) Robotic roommates: Visitors love this tabletop robot named ElliQ, who asks and answers questions, offers advice for keeping active and even writes poetry. HHL employees are less enthusiastic. While she may help to curb loneliness, she’s expensive, lacks functionality and, sometimes, just won’t keep quiet. Their solution is to pretend it’s time for bed: “Good night, ElliQ.” Also present in the lab, Alexa isn’t as cute as ElliQ, but she’s a problem solver. With simple commands, she can tackle a host of handy tasks like ordering groceries, setting medication reminders, locking doors and turning lights on and off. Plus, it’s one of the more affordable options in the home technology realm.

Bedroom

(1) All rise: Placing risers under couch or chair legs immediately transforms low seats into higher, manageable ones. Plus, they’re readily available and affordable.

(2) Help or hazard?: A handrail can help users sit up in bed or keep them from rolling out in the middle of the night. But it’s also easy to catch a finger or arm inside its bars.

(3) All right at night: Small motion detectors can automatically turn on the lights to help eliminate trips and falls during midnight bathroom visits.

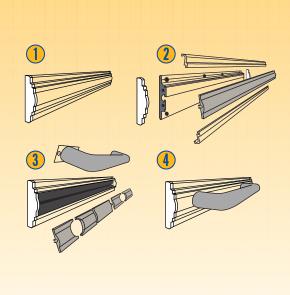

Mobius

Mobius is the premier product of the Healthy Home Lab. It’s an adaptable rail system that can be installed throughout a house and reconfigured as the user’s needs and abilities change.

Its components — including grab bars, handrails and stair assist devices — are easily attached, removed and repositioned with a quick snap. And when not in use, it looks like a decorative chair rail. The project is being supported by a $2 million grant and is on the cusp of commercialization.

HHL’s technical director, Jon Pearlman, calls Mobius the perfect example of taking a real-world problem — ugly grab bars that make homes look like hospital rooms and are difficult to install — and making an elegant, viable and marketable solution.