Subscribe to Pittwire Today

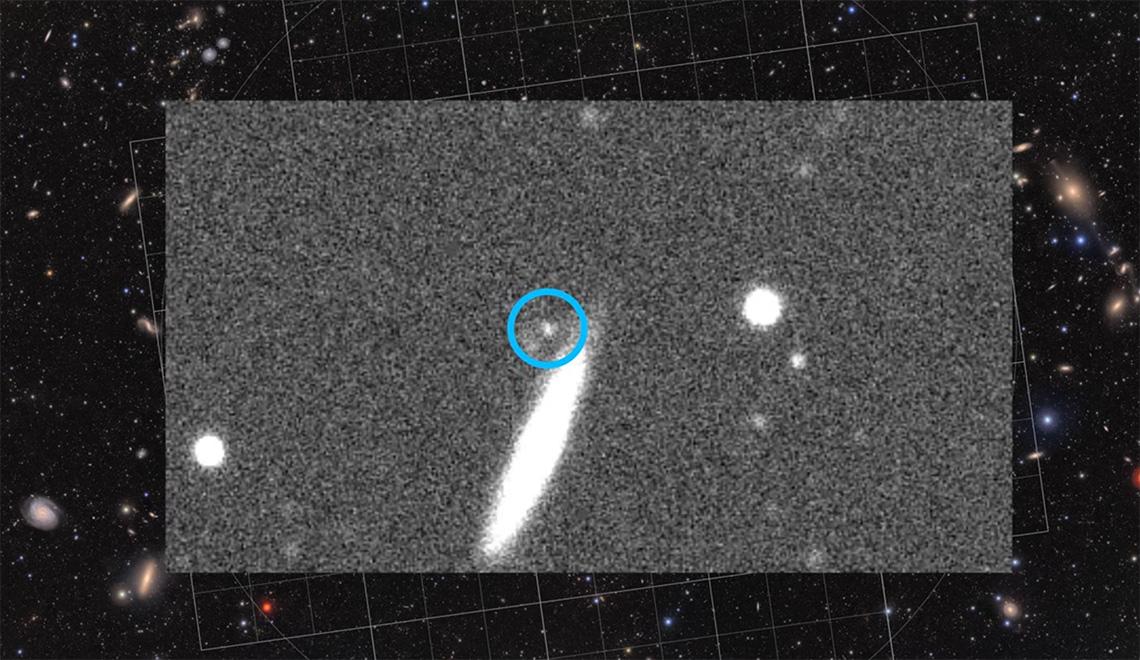

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.One of the first images of the sky from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory was so massive, so full of detail and data, that it would take 400 ultrahigh-definition televisions to show it in full resolution. Instead, more than 140 people saw just a sliver of the image taken from a cache of data dubbed “the treasure chest” during a June 23 watch party at Pitt’s Frick Fine Arts Building.

Made from a little more than 10 hours of observations, the section showed 10 million galaxies. That’s just 0.05% of the roughly 20 billion galaxies Rubin, situated atop a mountain in Chile, will capture during the 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University joined more than 300 institutions around the world at simultaneous watch parties, where the first images from the new observatory were shared with the public. Rubin will ultimately create a 10-year time-lapse view of the southern sky after taking 2 million images, which will yield 30 trillion measurements of the properties of billions of galaxies, stars and asteroids.

Sharing is central to Rubin’s mission — the observatory will make its data widely accessible to a diverse community of scientists as well as the public. The sentiment was echoed by Pitt and Carnegie Mellon researchers who talked about the importance of this new scientific endeavor.

“These data are for everyone,” Michael Wood-Vasey, chair of the board of the LSST Discovery Alliance and professor of physics and astronomy in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, said in an introduction before the images were released. “Everyone can follow along, from elementary school students to a scientist somewhere who doesn’t have access to a telescope.” They can all ask and attempt to answer some of the biggest questions about the universe.

Representing Carnegie Mellon was Tiziana Di Matteo, a physics professor and director of the McWilliams Center for Cosmology and Astrophysics, who led a panel discussion and gave the audience a chance to ask questions.

In the audience were space enthusiasts, school administrators and students — from high schoolers taking classes at Allegheny Observatory to PhD candidates and postdoctoral researchers.

Rob Rutenbar, Pitt’s senior vice chancellor for research, praised the project — funded by the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy and several substantial private donations — as an “amazing example of a public-private partnership.

The fruits of the partnership were a long time in the making. Event host Andrew Zentner, professor and chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, motioned to a photograph of the observatory with trucks parked in front.

“These are real pictures, right?” he asked. “Because I remember 10 or 12 years ago, seeing mock-ups and they’d always have trucks parked out front for scale.”

Wood-Vasey and Zentner were joined by colleagues and researchers from the department, including Jeff Newman, professor; Brett Andrews, research associate professor; and Mi Dai, research assistant professor.

Researchers in Pittsburgh, including Wood-Vasey and Newman, have been working on this project for two decades. During that time, they have developed tools to more accurately measure galaxy distances, turning Rubin’s images into 3D maps, and to improve the ability to detect changes between observations. They’ve also created new software to deal with sharing the massive amounts of data they’ll be receiving, including the flood of notifications whenever Rubin notices a change in the sky — which will happen about 10 million times every night.

Named after Vera C. Rubin, an astronomer who provided convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter, it’s fitting that new insights made possible by the observatory will be used by researchers around the world to unravel some of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics, including those surrounding the cause of the acceleration of the universe’s expansion, labeled dark energy, and the nature of the invisible dark matter that holds galaxies together.

Top photo by Rubin Observatory/NSF/DOE/NOIR Lab/SLAC/AURA/Hernan Stockebrand